Fair of face, highly intelligent and forever curious, the Mughal Emperor Jalal al-Din Muhammad Akbar, despite his lack of formal education, left a deep impress on India’s political and cultural arena in the mid-16th century. What he lacked in formal education was more than made up by the fates when it came to his debut as a pawn on the chessboard of Mughal politics.

At the tender age of nine, Akbar was inducted into politics with an appointment as governor of Ghazni, had an army at his command on the instructions of his father Humayun, and was betrothed to Ruqaiya Sultan Begum. By the time he was 14 years old, not only was the pair joined in holy matrimony, the young prince was expected to play an even bigger role in politics.

On the untimely death of Humayun in 1556, Akbar was swiftly enthroned as his successor as Shahanshah in Kalanaur in the Punjab. It was none other than Bairam Khan, the commander-in-chief of the Mughal army, and a powerful statesman, who took this critical step to protect the Mughal throne, already under threat by Sikandar Shah Sur. Bairam Khan was to serve as Regent to Akbar till he came of age.

Akbar watched and learned from Bairam Khan how to navigate the game of thrones by using all the cunning needed against powerful enemies to emerge as a victor. Akbar’s well-reputed military prowess in his mature years must surely have carried traces of these early lessons.

Having disposed of his need for Bairam Khan’s guardianship as he approached maturity, Akbar emerged as a fully competent ruler in his own right.

While his pursuit of stabilising the Mughal hold on India, between 1556–1605, required a vigorous military presence over the years, at the same time Akbar was acutely aware that he needed a son who would eventually take on the reins of empire. It was with this intent, after years of being childless, that the emperor sought out the spiritual intervention of the popular Sufi saint who resided in the village of Sikri, about 40 km away from the Mughal bastion of Agra.

Akbar, who was not greatly endeared with the ways of the Orthodox Islamic practices of the Ulema in his court, had a deeper affinity with Sufism, which is what guided him to seek the blessings of the Sufi saint Salim Chisti. When his appeal to the saint to grant him a son was realised with the birth of Jehangir in Sikri, Akbar’s joy knew no bounds.

As you approach the fortified city of Fatehpur Sikri, you can’t miss the pristine white marble façade of the beautiful shrine Akbar commissioned to honour the Sufi saint for blessing him with an heir to his throne. To create a more lasting connection with the Sufi saint, Akbar planned a whole new city around his shrine. Fatehpur Sikri served as Akbar’s spanking new administrative base, while still deeply connected to the old Mughal bastion of Agra.

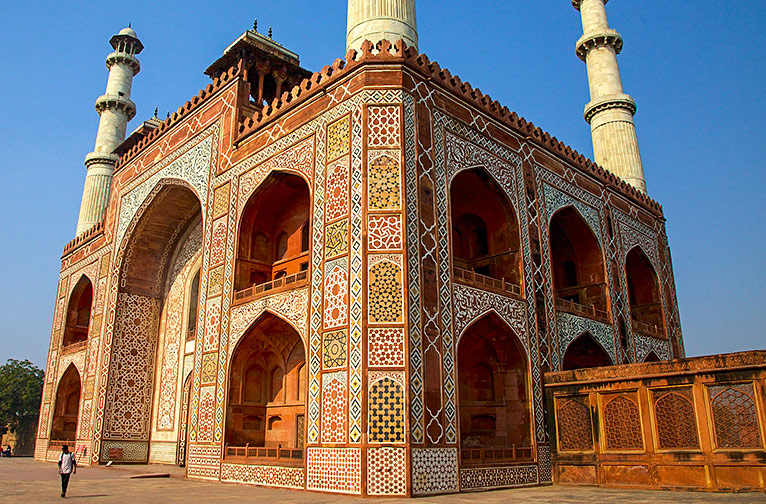

Constructed between 1571 and 1573, ‘The City of Victory,’ as Fatehpur Sikri is also known, is a reminder of Akbar’s successful Gujarat campaign. In fact, the massive Buland Darwaza, standing at a height of 54 m, is a memorial to that great victory. This commemorative gateway, built five years after the completion of the Jama Masjid, is considered ‘by far the greatest monumental structure of Emperor Akbar’s entire reign and also one of the most perfect architectural achievements in India’.

Akbar personally looked into the details of building the city, which is, in fact, cited as the first planned city of the Mughals. It is believed to have even influenced the building of another unmissable tourist attraction—Shahjahanabad/Old Delhi, dating to the later Mughal period under Emperor Shah Jahan.

Fatehpur Sikri has a wraparound wall on three sides and is fortified by towers and punctuated by nine gates. Of these, the best preserved is the Agra Gateway, the entry point for most tourists travelling to Fatehpur Sikri. The entire complex was quite self-contained to ensure its running smoothly as an independent capital city, including residential and private quarters for the royals and the courtiers, the army, the servants of the royal household, administrative and religious buildings, public spaces for leisure and entertainment, etc.

About 16 years later, Fatehpur Sikri was abandoned, believed to be largely due to water supply issues. Traders continued to use it as an important halt, as did some Mughal emperors, after the moving of the capital to Lahore in 1585.

Today Fatehpur Sikri is a UNESCO-acclaimed World Heritage Site. Though it certainly bears the scars of being abandoned so shortly after its birth, much of the original construction remains in pretty good shape and provides us excellent insights into the finesse of its architectural design and decorative features such as the calligraphy, stone carving, and jali work. These are exquisitely invested in the royal spaces, the religious and secular buildings, and living areas for the court, the army, and the servants of the king. They serve as a fantastic window to the works of architects and artisans dredged from all parts of Akbar’s far-flung empire who enriched the city with the ‘architectural idiom of their region’. Built entirely of red sandstone, quarried from an area behind the ridge Fatehpur Sikri stands on, the Mughal city showcases a stunning fusion of the lineage of Islamic and Hindu architecture.

A walk to the centre of the city brings you to the royal palaces, the administrative complex, and the Jama Masjid.

The Jodha Bai Palace is built entirely in red sandstone and is the largest building in the residential complex. The palace of Akbar’s beloved Rajput wife Jodha Bai (also called Mariam-uz-Zamani) is probably the oldest in the city, and the simple architectural lines reveal it as an early work. There is a noticeable Hindu influence throughout the building compared to other buildings in the city.

The Diwan-i-Am (Hall of Public Audience) features a small raised chamber which served as the emperor’s seat from where he would listen to petitions of his subjects and dole out justice to the public. It is directly linked to the imperial palace complex spread along a massive courtyard.

Wend your way northwards to the Diwan-i-Khas (Hall of Private Audience), also known as the ‘Jewel House’. The focal point here is the stunning central pillar, profusely carved with bands of geometric and floral patterns. Thirty-six serpentine brackets support the circular platform from which the enthroned emperor would hold court with special invitees; it is linked to each corner of the building on the first floor by four stone walkways. One of the most important matters of debate held here was Akbar’s desire for an inter-faith policy to ensure harmony in his kingdom. Representatives of different religions were invited to share the most compelling attributes of their faiths to this end. From these discussions emerged Akbar’s legendary Din-i-Ilahi, the new syncretistic faith which was rooted in the Sufi mystic ideals of Sulah-i-Kul meaning "peace with all," or "universal peace." As Akbar saw it, it referred to a harmonious coexistence of various religions. This inter-faith concept suited him well as the Mughal nobility comprised a mix of Iranis, Turanis, Afghans, Rajputs, and Deccanis. All religions were granted freedom of expression by Sulah-i-Kul, but no harm was permitted to touch the emperor or other religions.

The Daulat Khana-i-Khas, overlooking the Anup Talao, features the Khwabgah (House of Dreams), the emperor’s personal chambers located on the first floor. The Kutabakhana or personal library of the emperor, which is also part of this structure, featured about 25,000 manuscripts as ascertained by Mughal historian Abul Fazl. A room hidden behind the library was used as a secret meeting place by the emperor. Covered passages linked Daulat Khana-i-Khas to the various quarters in the harem and the Panch Mahal.

Unmissable structures worthy of an explore include the 5-storied Panch Mahal. Located near the Zenana quarters, it was probably used for entertainment and relaxation by the ladies of the harem. The Turkish Sultana’s House, placed at the corner of Anup Talao close to the Pachisi Board, is built entirely in red sandstone. Dated between 1565–1605, it is a fine specimen of early Mughal architecture. Both the interior and exterior of the house are densely carved. The carvings on the ceiling reflect Central Asian influences. The Rajah Birbal House, commissioned in 1571, bears strong Hindu influences throughout the design. Birbal was the only one of the legendary ‘nine jewels’ of Akbar’s court who lived in the complex in proximity to the emperor.

Spend tranquil moments at the Tomb of Sheikh Salim Chishti, set in the courtyard of the Jama Masjid, the earliest building constructed on the summit of the ridge. You will be blown away by the sculpted splendour of the saint’s tomb, a single-storied poem in pristine white marble, further enhanced in 1606 by Jahangir, Akbar’s son. Within its confines, the saint lies in rest under an ornate wooden canopy clad in a mosaic of mother-of-pearl. Devotees reverentially move along the covered circumambulatory passageway marked by beautifully carved stone fretwork set in an intricate geometric design. Of note here too are the white marble serpentine brackets supporting the sloping eaves around the parapet. To the left of the white marble tomb stands another tomb, but in red sandstone. It was raised to honour Islam Khan I, son of Shaikh Badruddin Chishti and grandson of Shaikh Salim Chishti; Islam Khan served as a general in the Mughal army under Jahangir’s rule.

After your explorations of Agra, a tour of Akbar’s beautiful tomb at nearby Sikandra is the perfect stimulus to know more about one of the most enlightened rulers of the Mughal period. Fatehpur Sikri should definitely be on your bucket list because this ‘ghost city’ has so much to offer in terms of understanding the ways of the legendary emperor. From his affinity with Sufism and keen desire for interfaith harmony… to his inclusive agenda for tapping the strengths of the various dominating players in the field, such as the Rajputs, through marriage alliances and collaborations… to his deep-rooted aesthetic sensibilities, Akbar’s worldview resonates well with us in the contemporary world.